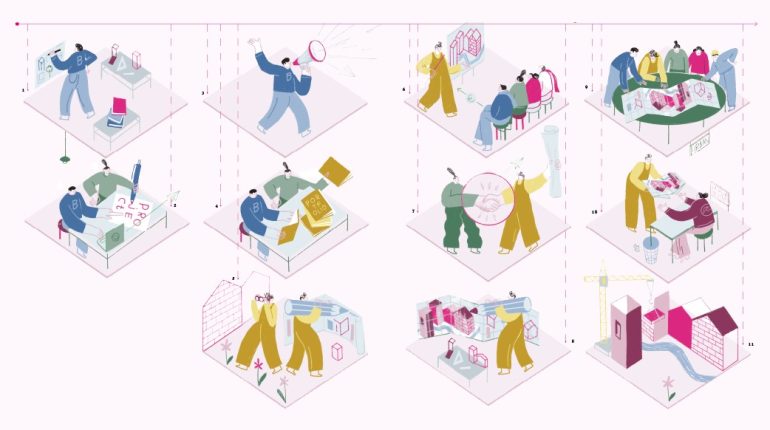

BMA recommendations are not binding. The need to convince compels BMA to repeatedly make relevant analyses, develop supporting arguments and communicate them clearly. This is BMA’s soft power, a form of urban design governance where the authorities act in a semi-formal manner, seeking to exert influence in ways other than through regulatory power. Of course, the whole body of legislation, regulations, established plans and enforceable standards are important — they ensure a minimum level of quality — but they are not enough. Achieving excellence requires alternative and usually more informal mechanisms.

In Brussels, the Bouwmeester assumes the role of soft power and as such differs fundamentally from, for example, the head of the planning administration, the decision-making bodies for a permit or a city’s ‘chief architect’. BMA operates from an independent position, both politically neutral and free of any hierarchical link to the other public institutions, the professional sector and civil society.

While the independence of the BMA mandate is certainly worth cherishing, it is also determined by the difficult balance that any Bouwmeester must seek. The political sphere can quickly see a Bouwmeester as a troublemaker and seek to sideline him or her; likewise, the professional sector might just as quickly attempt to dismiss him or her as a mere foot soldier with no credibility. Somewhere between these extremes are positions that the Bouwmeester can occupy to have a real impact.