WHY WE DO IT

Quality, transversality, transparency, three words that clearly define the BMA’s objectives. What do they cover? How is quality defined? What is meant by “working transversally”? Why is transparency so important at the BMA?

Quality

Architectural quality always requires a good debate.

BMA’s primary objective is to improve the quality of architecture across the Brussels region. But what is meant by “quality”? Today, quality no longer emanates from the classical canon, the diktat of a decision-maker or the mind of a so-called “creative genius”. Quality is not a pre-determined fact or a universal truth. Its meaning is rooted in context. What is meant by “architectural quality” therefore changes with context.

Context refers first and foremost to the urban environment. A building is never intrinsically “good”; it can “work well” in a given location, while elsewhere, the same architecture will stick out like a sore thumb. But context also has meaning beyond the physical reality of the urban environment. For example, social values can also frame discussions about quality. Quality is therefore not simply a “pretty picture”, which is why BMA argues in favour of an integrated approach to architectural quality. In other words, quality is the result of the convergence of very different elements: integration into the urban fabric, functionality and user-friendliness of the building or place, the social interaction created by the project, the sustainability of the project, the meaning the project generates for different target groups, and the economy of means. All of these facets, which constitute an integrated vision of quality, can be found in the assessment criteria for competitions supported by BMA.

The process which supports the development of the project and the degree to which this involves the users as well as the general population are also important factors for quality. Architectural quality is linked to considerations around the viability of the urban environment, meaning it cannot be divorced from social concerns. Good architecture should promote a good urban society, which is why architectural quality always requires a healthy debate. Regulations can ensure that a basic level is met, but they cannot guarantee the exceptional quality which we are pursuing.

One of the key roles of a bouwmeester is to ensure that this conversation about quality happens, and that it happens in the right way. Transparent organisation is essential in order to structure the conversation. Well-evidenced arguments that go beyond impulsive judgements are necessary to fuel the debate. The participants must take their responsibilities seriously and be firm in their positions in order to guarantee that decisions taken will be sustainable in the long term. When all of the above requirements are met, the conversation becomes useful, acquiring legitimacy and authority. The conversation becomes a foundation, and architectural quality becomes a shared value.

TRANSVERSALITY

Because we don’t work for anyone, we can work with everyone.

Working “transversally” is not just a fashionable term, it’s a necessity, especially in a city like Brussels, which is particularly spatially, socially and administratively complex. An urban region made up of diverse neighbourhoods with an ever-growing number of different demographic groups, it is governed by overlapping public authorities. Like every major administrative organisation, it is divided vertically into departments, agencies and companies, which can sometimes lead to a silo effect. At the same time, citizens have become active stakeholders in urban development policy and are playing a part in determining what their city should look like. Aside from the traditional Brussels neighbourhood committees and their umbrella associations, a range of new citizens’ movements are self-organising in a (semi-)professional manner, helping to shape policy and influence the future of the city.

Our society is faced with complex problems that we can no longer address from a single policy area, but for which we must together seek common sustainable solutions. An alternative public governance model is therefore necessary, one not based on experts working separately in specialist political arenas but rooted in cooperation, transcending hierarchy and breaking silos to experiment and seek innovative solutions.

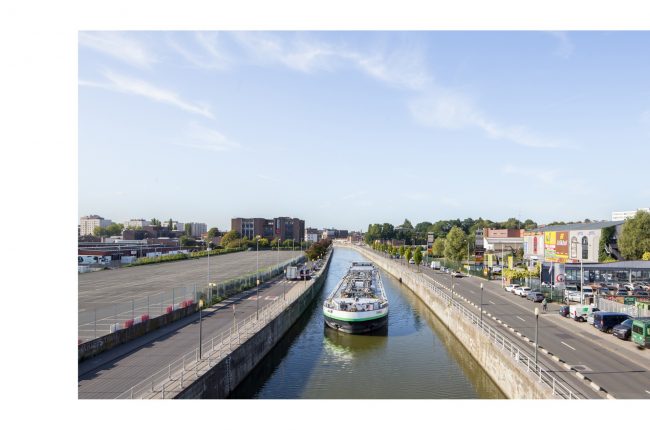

On the recommendation of BMA, in 2015 the government set up the Canal Team to oversee the development of the Brussels canal zone. This multidisciplinary team is made up of several different Brussels public administrations as well as neighbouring local authorities along the canal. By working horizontally across different institutions, the Canal Team operates in a manner that is new for Brussels, based on co-construction and project-based urbanism. This innovative and collaborative approach symbolises the development of a transversal planning culture in Brussels.

It is important for BMA to be able to take a transversal approach in all its work. The key to achieving this lies in occupying an independent position. This enables BMA to work with everyone, and allows us to build bridges between different stakeholders, from regional and local authorities, to the private sector and civil society. BMA aims to stay tapped into the city’s collective intelligence, regularly accessing it to gain a deeper insight and better overview beyond the boundaries of government institutions. This connectivity is one of the advantages offered by the way BMA positions itself as a hybrid organisation, operating both within and outside of the system.

TRANSPARENCY

A commitment to making planning processes accessible to the public has a long history in the creation of the Brussels region

A commitment to making planning processes accessible to the public has a long history in the Brussels region, as illustrated by the luttes urbaines (urban struggles) and the introduction in 1979 of an obligation to publicise debates relating to draft building permits through the Consultation Commission. Drawing on this tradition, BMA wants to make its workings as public as possible.

Transparency comes first and foremost from independence. BMA is not tied to any particular political affiliation, administration or stakeholder. This independence is a sine qua non condition of BMA’s ability to perform its duties: it must be able to express independent views on urban development projects in Brussels.

The recommendations issued by BMA are non-binding, and that is a good thing. It pushes us to come up with relevant analyses, to develop substantive arguments and to communicate them clearly in order to be credible and convincing. This is also referred to as “soft power”, a form of urban design governance in which the authorities are involved on a semi-formal basis, exerting influence in ways other than through regulatory powers. Legislation, regulations, development plans and standards are of course still important to ensure a minimum level of quality is met, but these alone are not sufficient. To achieve excellence, alternative and generally more informal mechanisms must be put in place. At BMA, we believe in these “soft power” principles and apply them in the way we operate.

Transparency also involves communication, particularly with regard to how we communicate competition procedures. This is why all competitions organised by BMA are announced through an open call, so that not only all potential candidates but also interested members of the public are informed from the very start. BMA also publishes the results of competitions on our website, by means of a Factsheet. From 2023, BMA takes transparency another step further and we also publish the bids of all candidates. In doing so, we ask that you respect the designers and their copyrights. Full or partial reproduction without permission from the authors is not allowed. Finally, BMA recommends that competition juries should be open to the public, in order to allow anyone interested to discover the projects and understand how they are assessed. The aim is to involve civil society earlier and in a more open manner whenever new plans and projects are launched.

We argue in favour of a relaxed and open approach which convinces everyone involved of the integrity of the process. Transparency goes hand in hand with open communication, which generally leads to greater trust and support. In turn, this stimulates the dynamics of urban development.