The Bruxellian sands are a sedimentary geological formation formed 45 million years ago during the Eocene period; the layers are made up of alternating sands and nodules of sandstone, sometimes ferruginous and formerly located in the bed of a sea – along the coast or in a delta. These sands constitute one of the conditions for the installation of a prosperous city: their use as a material for construction and industry, as well as the use of water from the river for consumption and production.

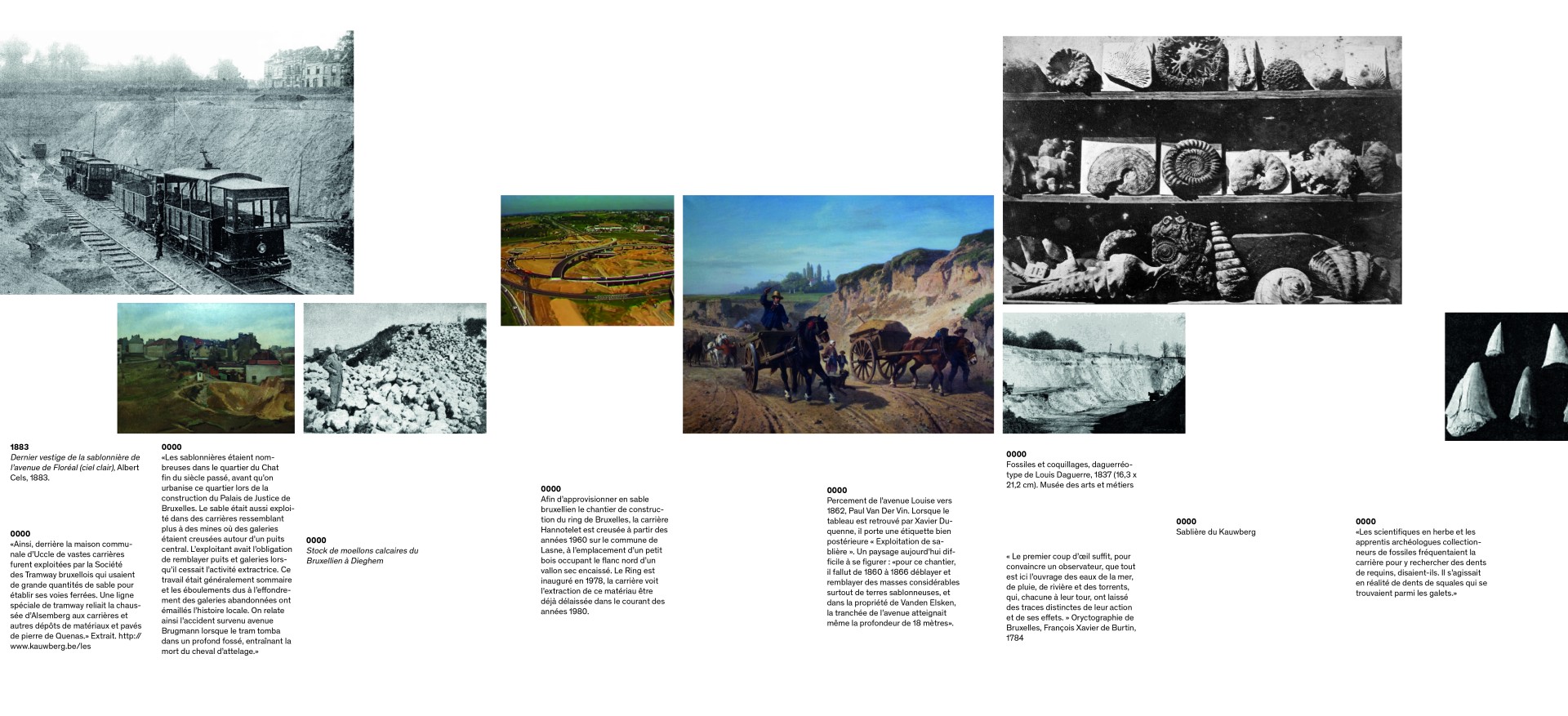

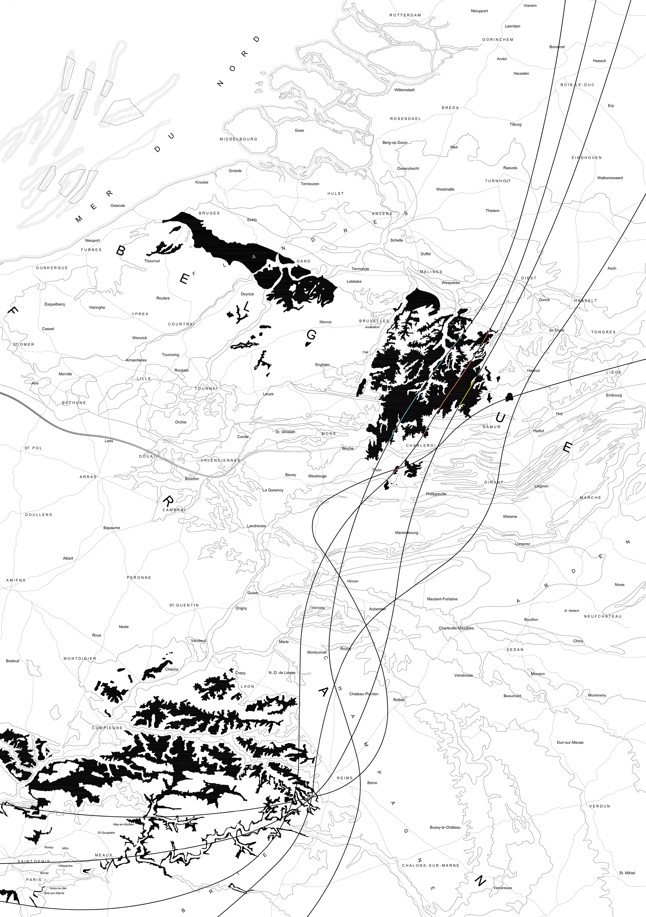

In his Oryctographie de Bruxelles (1784), François Xavier de Burtin, states: “The first glance is enough to convince an observer that everything here is the work of the water of the sea, rain, rivers and torrents, each of which in turn has left distinct traces of its action and effects. ” On several occasions, the author also mentions open or underground quarries dotted all over the city, often abandoned without backfilling; since the Middle Ages, the sandstone beds in the Bruxellian sands have been quarried to make lime, stone walls and cobblestones. More recently and even today, large sand quarries mark the landscape of the capital and its Brabant hinterland, often used for the construction of the capital’s infrastructure or its urban sprawl.

In fact, Brussels and its sands have a shared history that is ongoing; it is the history of co-manufacturing but also of co-alteration, which questions both the deep history of the human occupation of earth and our immediate past and future, our ways of inhabiting worlds and soils. In this research project, we postulate that the sands of Brussels are not only an inert and buried material, but also a living actor of human and urban techniques and cultures, reminders of which are visible in resurgences and outcrops, in the soil movements and urban landscapes that result from their use, in the constant filling and excavating works that shape the infrastructures of our territories, and in the pioneering and hybrid forms of nature that develop on its specific soils.

By resuscitating the care and attention given to what lies under our feet, From the Bruxellian to the Bruxellocene sets out to trace the long space-time evolution of the relationship between Brussels and its soils, to draw up an inventory of the expressions of these relations and to restore them on a cartography of the living that gives an alternative account of the interpenetrations between extractions and outcrops on the surface and alterations underneath; a small geological odyssey of Brussels which is an exploration of contemporary issues around land use and management, and also the possibility of better cohabitation with the mineral world.

“Sedimentation as a verb” is how Matthieu Duperrex proposes that we observe the world around us (1), as an opportunity to put the mineral order at the heart of the issues surrounding living things, which are all too often concerned with what is directly visible in the biosphere, in the environment and in the human body but which, at the same time, see the lithosphere as a collection of inanimate, eternal and buried objects or as glib metaphors for solidity. As Marcia Bjornerud (2) reminds us, rocks contain within them a multitude of events: “they are not in a state of being, but of becoming”. They urge us to re-mineralise our terrestrial, human and urban narratives and reweave the links between the convenience of the worlds that we populate and their cycles.

(1) Matthieu Duperrex, La Rivière et le Bulldozer, Premier Parallèle, coll. Parallel Notebooks, 2022

(2) Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World, Princeton University Press, coll. Focus on Climate, 2018

@Théo Larvoire

@Théo Larvoire

@Théo Larvoire